Non-Aspergillus mold infections are caused by molds other than Aspergillus. Read on to learn more about these infections and the fungi that cause them.

WHAT IS IT?

Overview

Non-Aspergillus mold infections are caused by a wide variety of molds that are not from the Aspergillus genus.

Because there are so many individual molds that cause these infections, scientists and healthcare providers often find it helpful to divide them into groups based on their appearance under a microscope.

- Mucormycetes (also called Zygomycetes) grow as broad, ribbon-like hyphae without septations.

- Hyaline hyphomycetes have either colorless or sometimes brightly colored colonies or conidia. Unlike the mucormycetes, these fungi typically have septate hyphae.

- Dematiaceous hyphomycetes have dark colonies or conidia due to dark pigments (melanin or melanin-like pigments) produced by the fungi. Like the hyaline hyphomycetes, these fungi usually have septate hyphae.

The list below represents the more common non-Aspergillus molds encountered in healthcare settings. There are countless fungi not on this list; it is important to ask your healthcare provider to help classify your fungal infection to see if it fits one of these groups.

- Mucormycetes include species of the genera:

- Mucor

- Rhizopus

- Rhizomucor

- Cunninghamella

- Saksenaea

- Apophysomyces

- Lichtheimia (formerly Absidia)

- Hyaline hyphomycetes:

- Fusarium

- Scedosporium

- Lomentospora

- Paecilomyces

- Acremonium

- Rasamsonia

- Penicillium

- Trichoderma

- Trichophyton

- Dematiaceous hyphomycetes:

- Alternaria

- Exophiala

- Curvularia

- Cladosporium

- Ochroconis

- Bipolaris

These fungi typically live in the environment—in the soil, on plants, and on decaying material like fallen trees. Humans are constantly exposed to these fungi, mainly in the form of fungal spores we breathe in every day. Sometimes, injuries associated with extreme weather (e.g., tornadoes), car accidents, and other traumatic events cause these fungi to be directly implanted (inoculated) into human tissue and cause infections.

Most non-Aspergillus molds are not likely to make us sick unless we have a medical condition or medical treatment that causes a weakened immune system. A compromised immune system is the highest risk factor for developing an infection with a non-Aspergillus mold.

The Burden of Non-Aspergillus Molds

Like most fungal diseases, infections due to non-Aspergillus molds are not well studied. As a result, we don’t know exactly how many people are affected by non-Aspergillus mold infections. However, we do know that the number of non-Aspergillus molds is increasing. Non-Aspergillus molds caused less than 10% of mold infections during the early 2000s. More recently, this number has increased to more than 1/3 of infections.

Outcomes

What is the prognosis for non-Aspergillus mold infections? Many infections affecting our skin or nails are mild. However, even these superficial infections can lead to serious consequences if not adequately addressed by a healthcare provider. In its worst form, non-Aspergillus mold can cause life-threatening infections. Doctors estimate mortality for patients with severe infection, especially immunocompromised patients, may be as high as 90%, depending on the circumstances of their infection.

This section of the website is focused on the invasive forms of non-Aspergillus mold infections. For a brief review of other forms of non-Aspergillus mold infections, see the two SPECIAL FEATURES: SUPERFICIAL INFECTIONS and IMPLANTATION MYCOSES.

SPECIAL FEATURE: IMPLANTATION MYCOSES

When fungi become implanted in the skin, typically because of trauma, implantation mycoses can result. These conditions often occur because of outdoor work. The CDC is tracking these conditions closely. To learn more about their occurrence in the United States, read this article.

When fungi become implanted in the skin, typically because of trauma, implantation mycoses can result. These conditions often occur because of outdoor work. The CDC is tracking these conditions closely. To learn more about their occurrence in the United States, read this article.

Eumycetoma

Eumycetoma is a specific type of chronic fungal infection of the skin and soft tissue (e.g., muscles). It is sometimes referred to as Madura foot or a mycotic mycetoma. More than 40 types of non-Aspergillus molds are known to cause this type of infection. The most common of these fungi are Madurella mycetomatis or M. mycetomatis, Trematosphaeria, Falciformispora, and Scedosporium.

Eumycetomas are common in tropical and subtropical parts of the world, though can occur outside of these regions. Areas with high numbers of eumycetomas are likely expanding due to climate change.

Infection usually occurs by minor trauma that breaks the skin and introduces fungi directly into tissue (for example, stepping on a sharp stick or thorn). Because fungi enter the body in this way, eumycetoma usually affects the foot and lower leg. If the immune system cannot control the infection, the infection becomes chronic. Over months to years, the fungi can spread to nearby tissue and cause scarring (fibrosis), swelling (edema or lymphedema), and sores. The infection can even infect nearby bones.

Chromoblastomycosis

Chromoblastomycosis is another type of chronic fungal infection of the skin and soft tissue. This type of infection is caused by melanized (darkly colored due to the production of pigment) fungi including Fonsecaea, Cladophialophora, and Phialophora. Like eumycetoma, chromoblastomycosis is most common in tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

Outdoor exposure, especially while barefoot, is a risk factor for this type of infection. Infection usually occurs after minor, localized trauma caused by vegetative matter like a thorn or a wooden splinter. Over months to years, a papule (pimple-like lesion) forms over the location of the injury. This papule will grow and develop wart-like (verrucous) scarring (hyperkeratosis).

Definitive diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis requires collecting some of the infected tissue (usually by a biopsy). Then, using a microscope, a doctor called a pathologist will look for specific signs of infection. The most infamous sign is the presence of “muriform cells” which look like a stack of copper pennies.

Early diagnosis and treatment are key for successful treatment. Surgical removal of infected tissue is the first-line treatment when the infection is small and localized to a specific area. Surgery at this early stage is often curative. More advanced infections are often too widespread to safely perform surgery. Advanced infections can be treated with prolonged courses of antifungal medications, though treatment success varies.

SPECIAL FEATURE: SUPERFICIAL FUNGAL INFECTIONS

Dermatophytosis is an umbrella term used to describe superficial fungal infections of the skin, hair, and nails caused by fungi called dermatophytes. There are many fungi that cause this type of infection, though Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton are among the most common. Dermatophytes can cause this type of infection because they can obtain nutrients from keratin, a common structural protein in the cells of our skin, hair, fingernails, and toenails.

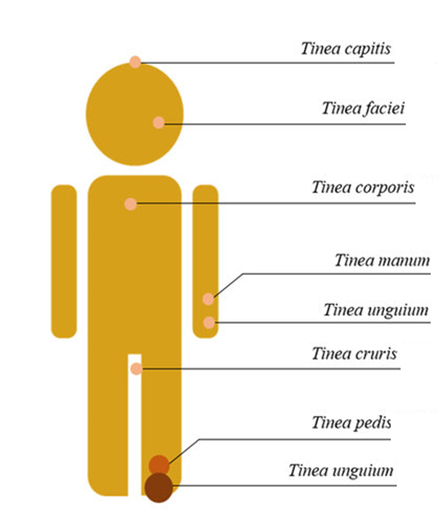

As shown in the image below, when different parts of the body get infected with dermatophytes, healthcare providers may refer to these infections based on their location.

- Tinea corporis

- Derived from the Latin word for “body.”

- Infects the arms, legs, and torso.

- Presents with an itchy (pruritic) patch of scaly skin often in a circular pattern. As the infection develops, the center of the patch may clear causing the infection to look like a ring. Due to the shape of this infection, it is often called “ringworm.”

- May be misdiagnosed as eczema or psoriasis.

- Tinea pedis

- Derived from the Latin word for “feet,” this is the medical term for athlete’s foot.

- Itching (pruritis) of the infected skin is the most common symptom.

- Skin flaking, skin thickening, and redness can also be seen.

- Excessive scratching may further damage the skin and increase the risk of a bacterial superinfection (a bacterial infection that occurs at the same location as the fungal infection).

- Tinea cruris

- Derived from the Latin word for “leg.”

- Affecting the folds in and around the groin. Sometimes called “jock itch.”

- Presents as itchy or painful scaling of skin around the groin, perineal or perianal areas, or buttocks.

- Tinea capitis

- Derived from the Latin term for “head,” and causes infection of the hairs (folliculitis) of the scalp.

- More common in infants and young children.

- Presents with itching, scaling skin, redness of the skin (erythema), and hair loss (alopecia).

- Tinea barbae

- Derived from the Latin word for “beard” Affects the beard and moustache area.

- Presents with itching, scaling skin, and pustules (pimples) around facial hair.

- Can also affect eyebrows.

- Tinea faciei

- Infecting the skin of the face, but not the beard and moustache area.

- It often spreads from fungal infections affecting other body parts.

- Tinea manuum

- Derived from the Latin word for “hand.”

- Affects the hands and fingers with symptoms similar to tinea pedis.

- Tinea unguium

- Derived from the Latin word for “nail.”

- This type of infection involves the finger and toenails. It is also known as onychomycosis.

- Initial infection causes abnormalities like nail discoloration, lifting or thickening of the nail, or splitting of the nail.

- Majocchi’s Granuloma

- This is a clinical subtype of dermatophytosis affecting hair follicles.

- Compared to the hair infections like tinea capitis and tinea barbae, this type of infection is usually deeper and produces a larger swollen nodule.

- Shaving of body hair, immunocompromise, and topical administration of corticosteroids are risk factors.

While these conditions are often managed with conventional topical medications, resistant and severe forms of dermatophyte infections have been noted lately. So it’s important to seek care for these infections and to be on the lookout for complex or resistant infections. To learn more about resistant dermatophyte infections, see resources from the AAD.

Frequently Asked Questions

No, the dematiaceous fungi discussed here are not toxic, black molds as described in consumer literature. The appearance of a mold under a microscope or in a culture dish doesn’t correlate with the color of a mold growing on a surface such as a wall. Molds can produce a range of colors on surfaces in the environment. There is a toxin-producing mold called Stachybotrys chartarum that is known as a black toxic mold. However, there is currently no test for that mold.

To gain clarity about the fungal colors as used in the lay press and why they are misleading, see our partner’s resource. Centers for Disease Control also have helpful resources on managing mold.

Nevertheless, if you are immunocompromised, it is important to take steps to reduce your exposure to molds in the environment. We will discuss that more under Risk Factors.

Again, the Indian lay press attempted to label a range of fungi by colors during the pandemic. The reason they called mucormycosis “black fungus” was because the infection caused tissue to break down (necrosis), which led to a black appearance of the skin. This color had nothing to do with the color of the fungus in laboratory cultures, Mucor tends to be gray to dark gray or brown in culture. To gain clarity about fungal colors as used in the lay press and why they are often misleading, see our partner’s resource.